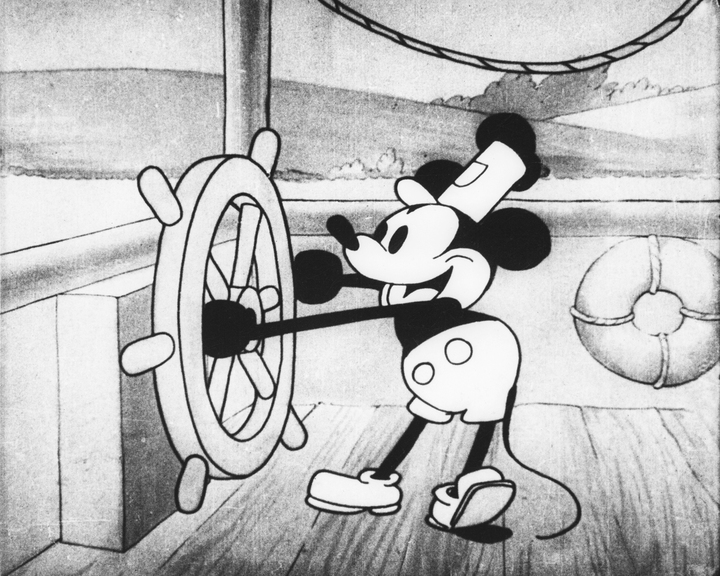

As you may have heard, on January 1, 2024, Steamboat Willie—the first successfully distributed Mickey Mouse cartoon—as well as the Mickey and Minnie Mouse characters themselves entered the public domain.[1] [2] [3] This subject has been getting a lot of attention, but despite several legal commentators having already discussed it, confusion continues to abound.

Disney is popularly perceived as having been responsible for Congress extending the total term of protection provided by the 1909 Copyright Act to 95 years, and that extension has been widely criticized as economically and culturally regressive.[4] Perhaps for that reason, Steamboat Willie and Mickey’s entry into the public domain was immediately met with a tidal wave of publicized non-Disney uses, including the announcement of a horror movie based on Steamboat Willie,[5] widespread posting of the original Steamboat Willie short to YouTube and other video hosting sites, grotesque non-animated art, and the announcement of a game with a noticeably similar aesthetic,[6] among others. But even though it is generally true that “the right to copy, and to copy without attribution once a copyright has expired … passes to the public,”[7] you still can’t quite do whatever you want with Mickey and the Steamboat Willie cartoon. The situation is much more complicated than that.

First, later portrayals of Mickey Mouse may still be protectable by copyright and owned by Disney. “Courts have recognized that copyright protection extends not only to an original work as a whole, but also to ‘sufficiently distinctive’ elements, like [] characters, contained within the work.”[8] Copyright also protects both a totally original work of authorship as well as “derivative works” that are “based upon one or more preexisting works… [that] recast, transform[], or adapt[],” the preexisting work by incorporating some new creative addition.[9]

Normally the topic of derivative works and works incorporating preexisting characters comes up with respect to adaptations by another creator and/or from one medium into another, but the same principle applies to adaptations by the same creator, or in this case The Walt Disney Company, into the same medium.[10] Disney has revised Mickey into several new versions over the years. These have included both design changes like swapping his solid black eyes for “pie eyes,” giving him gloves with 3 ribs, and coloring his shorts, shoes, face, and sometimes gloves, as well as additions to his character traits, such as his owning a dog named Pluto or his shift from a mischievous to a more good-natured personality.[11] These revisions may be independently protectable as derivative works if they involve a sufficient level of creativity. Although it is possible that the changes in any particular version may not be sufficiently creative to make them protectable, the standard only requires a “minimal degree of creativity” the required level of which is “extremely low.”[12] And the only way to test this would be by using one of those later versions of Mickey, waiting for Disney to sue or suing yourself if/when they threaten you, and engaging in a long and expensive court battle.

However, assuming Disney does own valid copyrights in the newer versions of Mickey, the legal protection those versions receive as derivative works is to the new additions rather than the basic, public domain aspects of the character (i.e. Mickey as a black cartoon mouse with light patches in the face and belly, who wears two-button shorts, and rounded shoes, and has ears represented by big black circles, and large eyes).[13] Because of this, you could still either use the original version of Mickey without infringing Disney’s copyrights or you could theoretically adapt the basic attributes of that original Mickey Mouse into a new design for Mickey, so long as it wasn’t too similar to any of Disney’s own later versions.

If you really want to use Mickey Mouse or any material from Steamboat Willie in a project, you would need to closely analyze the details of the project to determine whether any of it may infringe on Disney’s remaining copyrights and, even if it does, whether it may be entitled to any fair use defense. This inquiry would be extremely fact-specific for your individual project, and you should discuss your plans with a lawyer before proceeding.

Second, third party websites that host your projects may have their own private rules for addressing rights issues, which may result in their refusal to host or monetize your project using public domain material such as Steamboat Willie or Mickey Mouse, even if you aren’t actually infringing on Disney’s copyrights.

Web 2.0 sites that host user content enjoy protections from secondary liability for copyright claims if they provide a certain mechanism for rightsholders to have things removed pursuant to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”). And the DMCA provides certain protections for someone subject to a false or bad faith DMCA takedown.

But the content websites host is also subject to the website’s own terms of use, which the website owner dictates and which may also address copyrighted material uploaded by users. The website may also have its own methods of enforcing those terms of use apart from their DMCA mechanism.

For example, YouTube provides for a formal takedown-by-notice mechanism pursuant to the DMCA, which they call a “copyright removal request.” But as an alternative, YouTube also provides for its own automated mechanism that is not pursuant to the DMCA, which they call “Content ID” claims.[14] Suppose you had uploaded the now-public domain Steamboat Willie filmto YouTube in its original form. If someone like Disney were to submit a copyright takedown notice pursuant to the DMCA (YouTube’s “copyright removal request”), you would have a right to submit a counter notice to get the video put back online and may also have a right to sue the party that submitted the takedown notice for damages, costs and attorney’s fees, depending on the circumstances.[15] However, if the video were automatically removed by YouTube’s alternative Content ID mechanism, you would not have the same protections. This has apparently been exactly what has been happening with respect to copies of Steamboat Willie uploaded to YouTube: their Content ID system is automatically flagging the videos and taking them down based on Disney’s settings applied to their own older upload of Steamboat Willie to YouTube.[16] While YouTube’s Content ID system still allows users to object to a faulty takedown, YouTube may not be legally required to receive or respond to such objections, and a user would not have the same right to sue.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Disney still owns trademark rights in the name and design of Mickey Mouse, including his original form. “The fact that a copyrightable character or design has fallen into the public domain should not preclude protection under the trademark laws so long as it is shown to have acquired independent trademark significance, identifying in some way the source or sponsorship of the goods.”[17] Trademark protects consumers association of branding with particular sources of particular goods and services, rather than the right to copy a creative work. Also unlike copyright: trademark does not expire; it requires ongoing use; and it can have state common law protections in addition to federal protections.

Disney has twenty-one active registrations for the word mark “MICKEY MOUSE” for a wide variety of classes of goods and services, including specifically motion pictures (which includes online short videos), as well as games, books, and other print media.[18] Disney also has an active registration for the particular stylized design for the “Mickey Mouse” title used in Steamboat Willie and other early Mickey cartoons.[19]

And since 2007, Disney has used a logo for its Animation Studios that includes a brief animated clip of Mickey Mouse driving the boat in Steamboat Willie, which is also registered.[20] [21]

There are likewise various other registrations incorporating the classic Mickey Mouse design.[22]

Additionally, although registered trademarks receive better protection from the perspective of the trademark owner, registration is not a requirement—the federal Lanham Act offers some protection for unregistered marks as well as state common law. [23] So there may be still other aspects of Steamboat Willie and the original version of Mickey Mouse that Disney could theoretically argue are unregistered trademarks deserving of protection.

Trademark employs very different standards for infringement from copyright. It does not prohibit all unauthorized uses that copy the trademarks, but rather uses that are likely to cause consumers to be confused as to whether something was sponsored or endorsed by Disney or otherwise hurt Disney’s brand by diluting it as an identifier of Disney as the source of products or by tarnishing the reputation of the brand.

Determining whether your use of Mickey Mouse or anything else from Steamboat Willie is likely to lead consumers to believe Disney is affiliated with the project, dilute Disney’s branding, or tarnish Disney’s reputation would also require a careful, extremely fact-specific analysis of how you are using those materials in your project and in any planned advertising (including how you describe it online store listings, boxes, etc.). Again, you should talk to a lawyer about your specific plans if you intend to use Mickey Mouse or Steamboat Willie in your own project. (And remember: in Steamboat Willie, Mickey’s gloves may be off—but when it comes to protecting their IP, Disney’s gloves are always off.)

[1] Alison Hall, Lifecycle of Copyright: 1928 Works in the Public Domain, Library of Congress Blogs: Copyright Creativity at Work (Jan. 8, 2024), https://blogs.loc.gov/copyright/2024/01/lifecycle-of-copyright-1928-works-in-the-public-domain/ .

[2] I will refer only to “Mickey Mouse” going forward, but much of what is said applies equally to Minnie.

[3] Pete, the third recurring Disney character featured in Steamboat Willie, had first appeared in 1925 and already entered the public domain with little fanfare.

[4] See Copyright Term Extension Act, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Term_Extension_Act (accessed Jan. 13 2024).

[5] Gene Maddaus, ‘Steambowat Willie’ Horror Film Announced as Mickey Mouse Enters Public Domain, Variety (Jan. 2, 2024), https://variety.com/2024/film/news/steamboat-willie-horror-film-mickey-mouse-public-domain-copyright-1235849861/ .

[6] The game Mouse was announced in 2023, prior to Steamboat Willie’s entry into the public domain, but hasn’t yet been released. Jon FIngas, ‘Mouse’ is a first-person shooter inspired by vintage Disney, Engadget (May 11, 2023), https://www.engadget.com/mouse-is-a-first-person-shooter-inspired-by-vintage-disney-134113206.html . It could possibly have been waiting until 2024 to incorporate more explicit Steamboat Willie material than had been previously shown.

[7] Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23, 33 (2003).

[8] DC Comics v. Towle, 802 F.3d 1012, 1019 (9th Cir. 2015) (recognizing protectable status of the Batmobile as a character) (citations omitted).

[9] 17 U.S.C. §§ 101, 103(a).

[10] The Walt Disney Company would be recognized as the author or at least the owner of derivative versions of Mickey Mouse made by the studio’s cartoonists. See 17 U.S.C. § 201.

[11] Mickey Mouse Through the Years, The Disney Wiki, Fandom, https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Mickey_Mouse_Through_the_Years (accessed Jan. 11, 2024).

[12] Feist Publications Inc. v. Rural Telephone Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991); CDN Inc. v. Kapes, 197 F.3d 1256, 1257 (9th Cir. 1999).

[13] 17 U.S.C. § 103(b); Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., 755 F.3d 496, 501 (7th Cir. 2014) (holding that “The ten [Sherlock Holmes] stories in which copyright persists are derivative from the earlier stories, so only original elements added in the later stories remain protected.”) (rejecting the argument that the character of Sherlock Holmes and his earlier stories had not entered the public domain because the character’s arc was not completed until Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1920s stories, which were still under copyright at the time).

[14] What is a copyright claim?, YouTube, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/7002106?sjid=10483925206037264373-NA#difference (accessed Jan. 11, 2024).

[15] 17 U.S.C. § 512.

[16] See Disney is STILL Copyright Claiming Steamboat Willie Videos, Reddit (Jan. 10, 2024) https://old.reddit.com/r/videos/comments/193fgbd/disney_is_still_copyright_claiming_steamboat/ .

[17] Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales Inc., 481 F. Supp. 1191, 1196 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (citations omitted)(recognizing that Beatrix Potter’s character Peter Rabbit could be protected by trademark even though the copyright had expired).

[18] E.g. MICKEY MOUSE, Reg. Nos. 247,156 (IC 09, motion pictures), 315,056 (IC 16, songs, cartoon strips and books), 3006350 (IC 09, CD-ROM discs, Computer game programs), 3750188 (IC 09, audio and visual recordings featuring live action and animated shows, video game discs and cartridges, downloadable video game programs).

[19] MICKEY MOUSE, Reg. No. 247,156.

[20] WALT DISNEY ANIMATION STUDIOS, Reg. No. 6,846,660 (in International Class 41 for “entertainment services in the nature of production and distribution of motion pictures).

[21] Notably, although Disney does not have a trademark for the wordmark “SteamboatWillie,” some other industrious companies are currently attempting to register trademarks for the wordmark Steamboat Willie, one for toys in international class 28, and one for pocket knives in international class 08. U.S. Trademark Application Serial Nos. 98,078,702 (filed Jul. 10, 2023), 98355526 (filed Jan. 12, 2024).

[22] E.g. Reg. Nos. 3598848, 3580905, 5027809, and 4475448.

[23] See 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(A).